Every year in Britain, a quiet fracture runs through Muslim life. In one home, a mother begins fasting. In another, a city away, her sister does not. Cousins celebrate Eid on different days. Even within the same family, some are still fasting while others are already feasting.

The cause is not disagreement over faith, but the sky.

The Islamic calendar depends on sighting the first crescent Moon. Different countries see it on different nights. For decades, many UK mosques have relied on announcements from abroad, leaving communities divided over when Ramadan begins and when Eid arrives.

For Imad Ahmed, that division became impossible to ignore.

Now a PhD researcher at the University of Cambridge, Ahmed grew up watching British Muslims argue each year over dates that were meant to unite them. “I saw families split at the most sacred moments,” he said.

“People weren’t disagreeing about God. They were disagreeing about geography.”

That experience became the foundation of his academic work. Ahmed’s research focuses on the Islamic lunar calendar in Britain – and how a community rooted in the UK can still end up governed by skies thousands of miles away.

“My dream is that Muslims across the UK can celebrate together,” he said.

“Muslims once had a deep relationship with astronomy. I want us to move from Moon-fighting to Moonsighting to Moon-uniting.”

From that vision, the Moonsighters Academy was born.

From divided skies to shared horizons

Led by the Universities of Leeds and Cambridge, the nine-month public engagement programme trains communities to carry out their own lunar observations in Britain. It blends online learning with in-person workshops and outdoor stargazing, equipping everyday people to host local “moon nights” in parks, school fields and mosque courtyards.

Its goal is both practical and symbolic – to give British Muslims the tools to sight the Moon at home, reduce confusion around religious dates and create a shared national rhythm for Ramadan and Eid.

Earlier generations in the UK often lacked the resources to conduct regular observations, compounded by cloud cover and limited access to equipment. As a result, many communities outsourced their calendars. Over time, this produced a patchwork of practice, with mosques following different countries and families celebrating on different days.

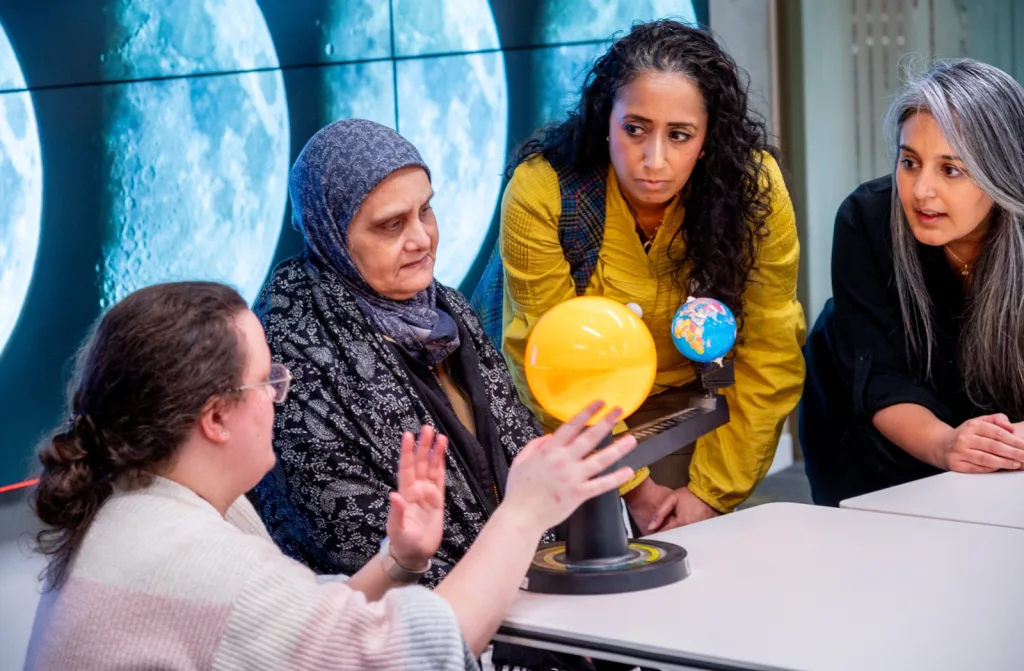

The academy’s first cohort gathered this month for a two-day residential at the University of Leeds. Thirty-eight participants travelled from across the country, including imams, schoolteachers, scout leaders, parents and a grandmother. They came from Bradford, Birmingham, Rochdale, Teesside and Bristol. The group is evenly split between men and women.

Some participants said their interest in the Moon began after having children, as they tried to explain the rhythms of Ramadan. Others traced it to the pandemic, when nightly walks made stargazing a quiet comfort. What unites them is a desire to bring others with them.

Astrophysicist Dr Emma Alexander, research fellow at Leeds and project co-lead, said the academy challenges who gets to “own” science.

“One of the joys of astronomy is sharing it,” she said. “This programme gives people the tools to connect their communities to the cosmos. It also shakes off stereotypes about who astronomers are.”

She added that she is especially excited by the number of young women involved. “They are part of our next generation of excellence in British science.”

Naz Shah, MP for Bradford West, who took part in a leadership panel at the launch, said: “The work being done here is second to none. It’s inspiring.”

For Mohammed Attaur, founder of the Rochdale Science Initiative, the project speaks to a real community need. “It connects faith, science and culture,” he said. “By the end, I want to lead a moonsighting group in my town and build something that lasts.”

Shemanara Haq, a community activist from Teesside, described the academy as transformative. “It didn’t just share information. It built confidence and real connections. I’m taking this back to my community with purpose.”

Sofia Dawoodji, a grandmother who develops educational resources for schools, called the prospect of a unified calendar “groundbreaking”.

“This is a first for the UK,” she said.

As Ramadan approaches, Ahmed’s idea is moving from theory to practice.

Across rooftops, parks and playgrounds, families may soon gather together, eyes lifted, waiting for a thin curve of silver.

When the crescent appears, it will not only mark the start of Ramadan. It may also mark the beginning of a new chapter in British Muslim life – one written not in distant time zones, but in the night sky above home.