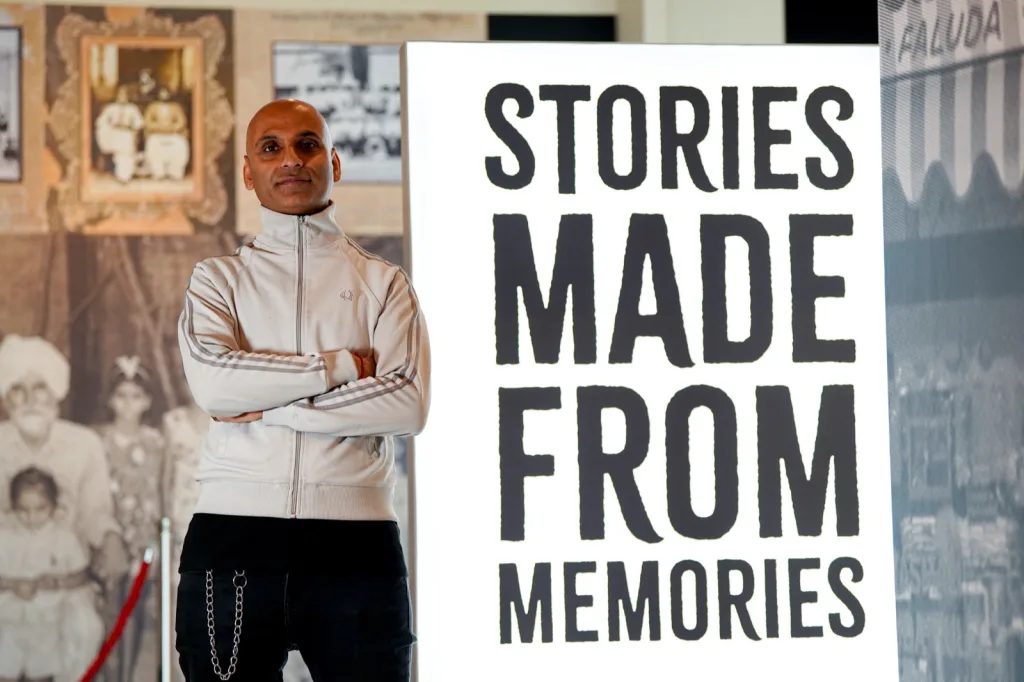

British South Asian artist Hardish Virk is asking families across the UK to open their photo albums, cassette boxes and memory drawers, issuing what he calls an “urgent” appeal for ethnically diverse communities to share their stories of growing up in Britain at a moment when hate crime and divisive rhetoric are again on the rise.

His call comes alongside the launch of ‘Stories That Made Us – Roots, Resilience, Representation’, a major new exhibition at Coventry’s Herbert Art Gallery & Museum that traces more than 50 years of South Asian life in Britain through lived experience rather than official record.

The timing is deliberate. Government figures released in October show a 6% rise in race hate crimes and a 3% increase in religious hate crimes across England and Wales over the past year, excluding Metropolitan Police data.

For Virk, those numbers are not abstract trends but a warning.

“This exhibition has been almost 30 years in the making,” he said. “But the need to share it now is urgent. Division and fear are rising again, not just in the Midlands but nationally.

“We need spaces where communities come together to share personal stories and family histories. They shape identity, belonging and how we see each other.”

At the heart of the exhibition is Virk’s own family history and an archive of more than 1,000 South Asian artefacts collected over decades.

Combined with his father’s original writings, political papers and photographs now held in Coventry Archives’ Virk Collection, it forms one of the UK’s most significant South Asian cultural collections outside London. Rather than presenting these materials behind glass, the exhibition immerses visitors in four reconstructed environments that echo everyday life across the decades.

The journey begins with Passport Control (1968), a reconstruction of the Virks’ arrival in Britain, surrounded by first-hand oral histories, archival footage and newspaper headlines.

The language may be decades old, but the debates feel strikingly current. From there, visitors step into a Living Room (1970s), recreating the Coventry home where Virk’s father, Harbhajan Singh Virk, helped organise anti-racist marches and workers’ rights campaigns. The domestic becomes political, showing how activism was woven into everyday family life.

The Bedroom (1980s) captures the tension and creativity of teenage British South Asian identity, mixing posters, books and music with a documentary film that blends new interviews and original VHS footage. The final space, Radio Studio (1990s-2010), celebrates the work of Virk’s mother, Jasvir Kang, a poet, author and radio broadcaster whose pioneering programmes gave voice to the rights and struggles of South Asian women at a time when such conversations were often sidelined.

Wrapping around the gallery walls is a pictorial timeline charting 425 years of shared British and South Asian history, from colonialism and Commonwealth migration to the present day.

It underlines a central argument of the exhibition: South Asian communities did not simply adapt to Britain, they helped shape it, driving postwar industry, cultural life and political change.

Visitors complete their journey by leaving a handwritten memory or reflection. With permission, some of these will inform the next phase of the project after the exhibition closes in May 2026.

Virk describes this as the seed of a wider ambition: a living museum of South Asian stories rooted in Coventry, where one in five residents identifies as Asian or Asian British, nearly double the national average.

The exhibition is supported by a major engagement programme and a South Asian Cultural Ambassadors Scheme, whose oral histories feature throughout. Shaniece Martin, who leads the scheme, said the personal nature of the stories was key.

“The experiences we’re sharing from the 60s, 70s and 80s feel painfully relevant again today,” she said. “When you hear someone’s real story, it becomes much harder to repeat stereotypes. We want people from across the South Asian diaspora, including Kenya, Uganda and beyond, to see themselves here and add their stories for future generations.”

Marguerite Nugent, cultural director at Culture Coventry Trust, which operates the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, said the exhibition’s strength lay in its ability to connect across backgrounds. “All visitors will find unexpected overlaps with their own lives,” she said.

“It has real potential to encourage connection and togetherness at a crucial time.”

Made possible with support from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Stories That Made Us is both an archive and an invitation. As Virk puts it, “This is my family’s story, but it’s also a conversation starter. We want communities to celebrate multicultural Britain, while challenging divisive language wherever it appears.”

‘Stories That Made Us’ – Roots, Resilience & Representation. The project, split across four rooms, is the blueprint for the wider ambition of a living museum of South Asian stories in Coventry, where one in five residents identifies as Asian or Asian British, nearly double the national average. It features:

- Passport Control (1968) – a reconstruction of the Virks’ arrival in Britain, surrounded by first-hand oral histories, archival footage and newspaper headlines echoing debates still heard today.

- Living Room (1970s) – a recreation of the Coventry home where activists met to organise anti-racism marches. It includes one of two new film installations by Manjinder Virk (Riverbird Films), starring Bally Gill.

- Bedroom (1980s) – a teenager’s room exploring British South Asian identity through posters, books, music and a documentary film mixing new interviews with original VHS footage.

- Radio Studio (1990s–2010) – which celebrates the work of Hardish’s mother, Jasvir Kang, poet, author and radio broadcaster, whose groundbreaking work spoke about the rights and struggles of South Asian women.