The appointment of Professor Adeeba Malik CBE DL as the next Lord-Lieutenant of West Yorkshire marks a turning point for one of the oldest offices in Britain.

When she formally takes up the role in December, she will become the first woman of South Asian heritage to serve as a Lord-Lieutenant anywhere in the UK.

That alone carries profound significance: it signals that even the most traditional institutions, once closed to large sections of society, can evolve to reflect the communities they serve.

The role itself is centuries old. Once charged with raising the county militia, the Lord-Lieutenant now represents the monarch at civic and ceremonial events, from organising royal visits to recognising local volunteers.

It is a post rich in symbolism. Whoever holds it becomes a bridge between crown and community, embodying recognition and legitimacy in moments of celebration and commemoration alike.

In a diverse county like West Yorkshire, home to some of the largest South Asian and Muslim populations in the country, that symbolism has never mattered more.

For many people whose heritage, faith or origin has too often been cast as “other,” seeing a person from a minority background step into one of the most visible ceremonial posts in the land counters a narrative that power, dignity and national belonging are exclusive.

This is not simply about optics. The timing of her appointment coincides with a moment of rising tension in Britain, where far-right movements, anti-immigrant sentiment and identity politics are exerting real pressure on social cohesion.

Representation and renewal

Professor Malik’s longstanding work in inclusion, diversity, and cohesion equips her to reach lines of trust and legitimacy that might not always be possible for less representative figures.

It’s anticipated her appointment could deepen the relevance and resonance of the Lieutenancy among underrepresented communities.

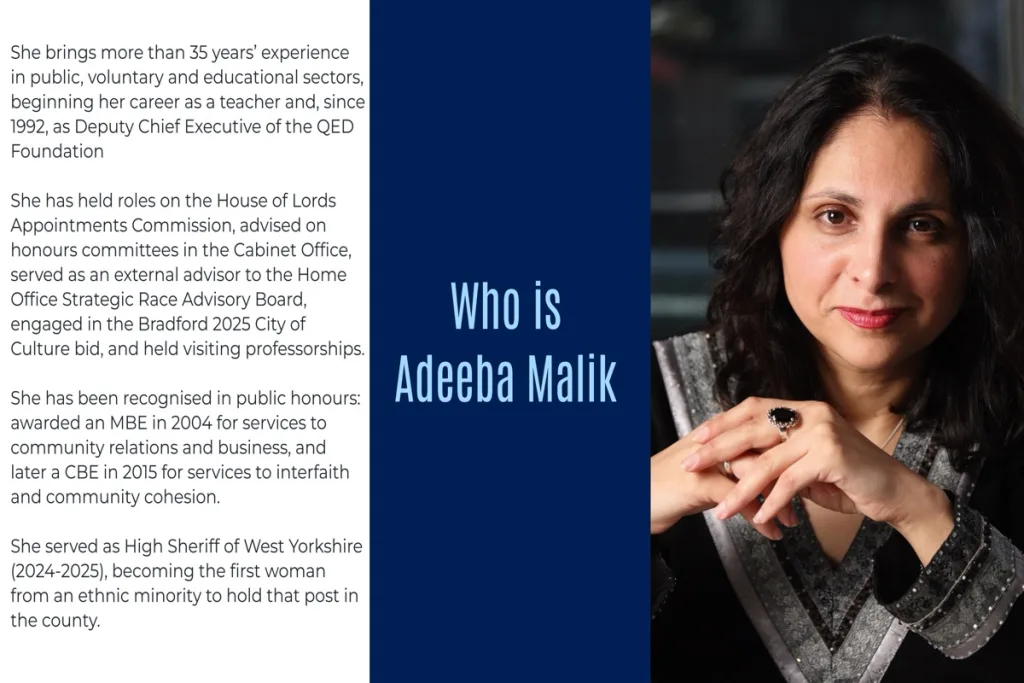

Born and raised in Bradford to Pakistani parents, Professor Malik built her career in education before spending more than three decades at the QED Foundation, a charity dedicated to social and economic inclusion.

Along the way she has advised governments, sat on national commissions, held academic appointments, and served as High Sheriff of West Yorkshire. Recognition followed; an MBE in 2004, a CBE in 2015, and she has long been a Deputy Lieutenant of the county.

Her appointment is therefore more than symbolic. It provides an opportunity to reconnect a venerable institution with communities who have often felt invisible in the civic sphere. For young people in particular, seeing a woman of Asian heritage in such a role is a powerful reminder that public service is not reserved for a narrow elite.

Her appointment is a landmark for Britain. It shows that even in the rituals of monarchy, tradition and diversity can coexist. It reminds us that civic identity is strengthened, not diminished, when new voices step forward; and it offers a signpost for what a modern, plural Britain can look like when institutions choose to reflect the country as it really is.